Text by Sean O’Toole

What distinguishes the migrant from the exile? Is it simply a matter of language, as émigré Russian Jewish poet Joseph Brodsky proposed at a literary conference on exile in 1987? The condition we call exile, insisted Brodsky, “is, first of all, a linguistic event”, one that produces a word more easily foisted on writers and artists than those desperate masses who, “whatever their motives, origins, and destinations,” opt to abandon home for elsewhere. All of which, remarked Brodsky, makes it very difficult to talk about the plight of the artist in exile with a straight face. Exile, the condition of living away from one’s home or country, whether through force or choice, is a loaded noun. It is loaded precisely because, to borrow a phrase from Iranian-born Sepideh Mehraban’s personal lexicon as an artist, it veils the truth of events.

Mehraban shares with Brodsky a distance, but not indifference, to the word exile. Brodsky’s suspicion that the word exile is “loaded with a possibility of self-aggrandizement” summarises Mehraban’s own misgivings. Why use a noun connected to so many upheavals and traumas to describe her particular situation? After all, she voluntarily settled in Cape Town in 2012 with the intention of furthering her painting practice after completing a master’s degree at Alzahra University, Tehran. She is free to return home. Why cast a veil over what is clear and apparent? “I will always be Iranian. I grew up there, even though I’ve lived here for a decade. My family is still there. I am very much Iranian.”

And yet, as Mehraban hesitantly admits, she is also an exile, or somehow feels like an exile. Her ambivalence is quite natural. “Origins trouble the voyager much,” wrote the exiled South African poet Arthur Nortje in 1967, shortly after settling in Canada, “those roots that have sipped waters of another continent.” The Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, himself an exile living in New York, was an admirer of Nortje’s poetry, recognising in it something of the contradictions that frame exile and memory: “The act of remembrance makes wanderers of us all, helping us build communities out of skeins of desire and nostalgia, feelings which inevitably succumb to the logic of reality.”

The logic of Iranian reality, in particular the lack of correspondence between the country’s written history and Mehraban’s personal history, came into clear focus during her studies at the University of Cape Town. Early into her studies, influenced by her separation from home, Mehraban began to parse her memories of family and home. Her earliest paintings presented family photographs and other visual markers of her Iranian identity, notably newspapers, sunken in fields of abstract colour. The work leaned into Gerhard Richter’s formal method of hazily reproducing black and white family photos in a series of paintings from the 1960s. Additionally, she overlaid her compositions with skin-like layers of glue, a process informed by the formless paintings of Penny Siopis, another formative influence.

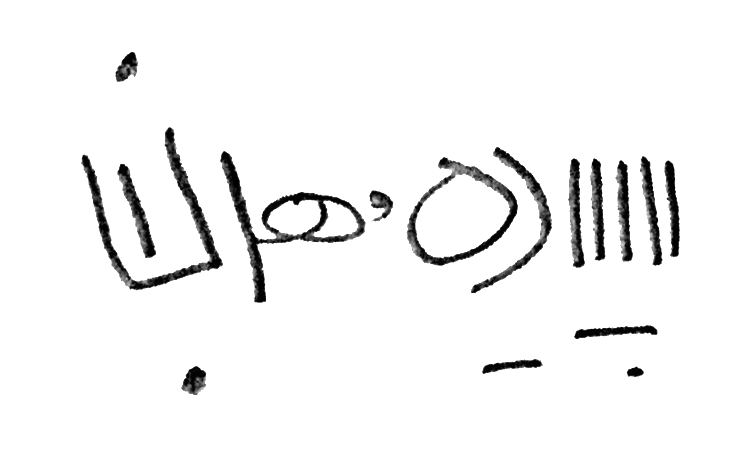

This additive method of painting, of layering images, remains central to Mehraban’s practice. It informs the artist’s process in her recent agitprop canvases featuring tonally muted bands on pink and grey-blue imagery layered over, and sometimes juxtaposed against, screenprinted images reproduced from four editions of the Persian-language daily newspaper Ettela’at. All the newspapers are dated 1979 and detail key events from the Iranian Revolution. This populist and nationalist rebellion of Marxists, Islamic socialists, secularists and Shi’a Islamists culminated in the toppling of the Persian monarchy in February 1979, only to be succeeded by an Islamic fundamentalist-led theocracy.

Mehraban was born during the rule of Ruhollah Khomeini, a conservative Muslim who supressed feminist voices, enforced Islamic dress codes and Islamized the educational system. In the manner of liberation elites everywhere, Khomeini’s role in the 1979 revolution was exulted and, latterly, amplified through erasure. Erasure and concealment are key words in Mehraban’s personal lexicon as an artist. It was while working on her second MFA that Mehraban recognised the agency of these two words as viable leitmotifs in negotiating her evolving practice. Toggling between personal photos and public documents, she noticed slippages between the official history of the Islamic Republic of Iran and her personal memories of home. For example, her school textbooks excluded the stories of women who participated in 1979 revolution but who did not support the Islamic regime of Khomeini, women she knew and grew up amongst. Official newspapers, she recognised, reproduced historical images of the revolution that had been doctored to elide inconvenient truths.

This veiling of the truth, once recognised and theorised, provided Mehraban with a viable conceptual tool for her academic research as well as a defining verb to describe how she paints: veiling. Mehraban is interested in erasure and concealment, and her paintings manage to visualise this through veiling. “My mark making does not signify factual information,” Mehraban explained in her MFA thesis, “but rather emphasizes inaccuracy.” Differently put, her layered canvases reproduce the error or glitch by serially reproducing it, by piling wreckage upon wreckage, as Walter Benjamin put it. There is an ethical imperative to this process of veiling:

I see the canvas as if it were skin that is veiled by materials, which I apply to it. It then embodies naked flesh and female sexuality, which, like histories, must be veiled. The surfaces of my paintings after paint is applied become like ruptured skin that bears witness to the concealment of Iranian women’s bodies and their liberal movement.

While painting remains central to Mehraban’s conception of her practice as an artist, her artistic lexicon additionally encompasses the word translation. ‘This is not Propaganda’ includes two hand-woven carpets produced in India. Each carpet translates fragments of her paintings, focussing the viewer on her vivid marks. Each carpet is composed of 20 differently coloured fibres, each hand-dyed. The uneven and distressed surface of the carpets represents a further translation of Mehraban’s paintings by her collaborators in India. The exhibition additionally includes a number of found carpets that function as substrate for her hand-generated paintings and screenprints. These worn carpets are a resonant site and material on which to stage her enquiries into the damage and destruction of Iranian history, and to articulate her admiration for the ability of ordinary people to prevail.

But I still haven’t addressed the agency of exile in negotiating Mehraban’s work. Perhaps it is through common usage, the word exile has come to propose a condition framed by loss – loss of home, loss of innocence, loss of roots. But exile can be generative too. The Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, who spent much of his working life in New York, wrote about this in 1984: “Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two, and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that—to borrow a phrase from music—is contrapuntal.” While Iranian history is the visual substance of Mehraban’s work, a contrapuntal perspective of exile informs her intellectual concerns. Like Iran, South Africa has a complex history grounded in unresolved trauma. Both have witnessed social unrest and student rebellions. “The student uprisings and protests are characterised by the traumatisation and upheaval of ordinary lives,” Mehraban has observed. “In both countries, protests are indicative of a need for political change and transformation.” Exile may be a loaded word, a noun vested with the capacity to veil the truth of events, but it can also, as Said suggests, “diminish orthodox judgment and elevate appreciative sympathy”.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and editor based in Cape Town