Until The Lions Have Their Own Historians, The History Of The Hunt Will Always Glorify The Hunter.

Until The Lions, feature eight works of mixed media on found carpets and draws its name from a famous line in Chinua Achebe’s seminal work Things Fall Apart.

In this series, as with her academic work as a PhD candidate at Stellenbosch University, Mehraban focuses on recent Iranian history, exploring it through text, figurative works and abstraction, often drawing on the grid format of newspaper as a source of inspiration.

Mehraban delves specifically into a heady and turbulent time in her birth country’s past - the 1979 revolution, a populist and nationalist movement consisting of Marxists, Islamic socialists, secularists and Shi’a Islamists. These diverse groups united to overthrow the monarchy but instead of a democracy ushered in an Islamic fundamentalist-led theocracy under Ruhollah Khomeini.

For Until The Lions carpets provided the ideal surfaces to work with as a means by which begin her chosen tactic of the overlaying and veiling of paint as a means of expressing layers of existence and experience.

“These are objects that embody and convey personal stories, they are symbols of the private and intimate that carry the stains of use. The damage and destruction of history - and our ability to prevail - are contained and represented by these beautiful artefacts,” says Mehraban.

These carpets are deeply personal yet Mehraban brings them the public space for inspection as evidence of the ordinary lives of those involved and affected by political change and unrest. By using these rugs as canvases she further references her own roots while asking whether a canvas can ever be totally blank. For Mehraban we are both separate and inseparable from our past.

“I’m interested in the personal experiences of people who have been caught up in political turmoil…how these personal histories are not necessarily told in textbooks or taught in schools or via official histories. In a way, I’m using art to bring back these memories.”

Included in the show is a video piece made in collaboration with studio mate Kathy Robins and delves into issues of environmental, land and socio political significance in post-apartheid South Africa and post-revolutionary Iran.

Robins is a vastly experienced artist with postgraduate qualifications from both Michaelis School of Art and Parsons School of Design in New York. The artists drew from Persian paintings, hunting scenes from ancient manuscripts and from their own personal histories to narrate the contemporary issues of both Iran and South Africa and stage an animated parody on propaganda and censorship.

The collection is an elaboration of the themes Mehraban interrogated in 2018 with her curatorial debut, Cape to Tehran. Inviting 19 artists from Iran and South Africa to respond to their experience of political change, Mehraban tasked the collective to study personal impact as well as the shared experience of intergenerational trauma and inherited change.

Now, by retracing her steps and digging up the stories she grew up believing, Mehraban questions our tendency to prefer official accounts to our own, more ephemeral yet arguably more keenly felt personal experiences.

Here she pits personal histories against public histories and homes in on the discrepancies between what is happening and what governments say is happening, where propaganda is used as a tool of oppression and ignorance.

This deliberate obfuscation speaks to the show’s title and reiterates Mehraban’s point that history and the past are not one and the same. History is a story we are told, usually by those who manage to speak loudest.

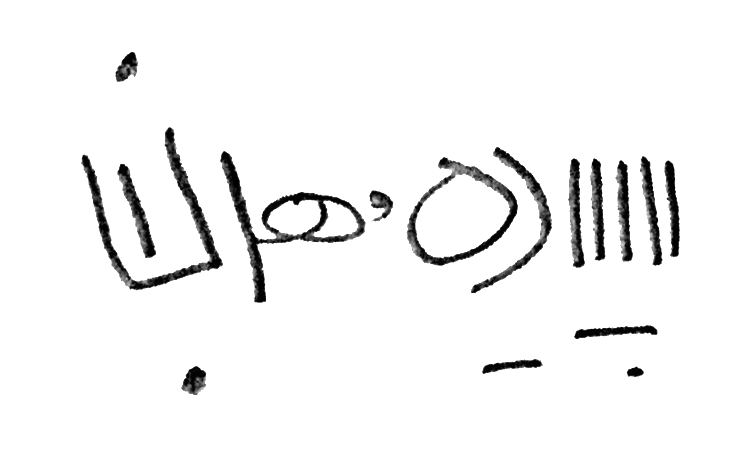

Mehraban’s materials act as veils, abstracting and obscuring her statements so that they become questions instead. Her use of glue poured freely over the rugs both covers and works as a new surface on which the artist screen prints newspaper articles.

These fragmented, mostly illegible reports are doubly oblique. Scraps of reports that were made up largely of tampered information are obscured by Mehraban’s mark making, replicating the acts of censorship. What can be made out is not trustworthy. We can’t know what is true and dependable information, leaving us to rely on instinct and our own private and emotional responses.

“I’m asking the viewer to look through these layers and make their own story. My goal is to challenge the idea that someone or some entity can tell you what happened to you. It’s really critical to have these conversations, especially in places where the conversation is so highly politicised.”

Like a historian relying of fragments of unreliable testimony trying to piece together a story that makes sense, Mehraban’s works are like puzzles. But there’s no end to this one.

“Like the big carpet full of holes, we might try to fix the holes but, in truth, they are there forever. They are part of us.”